What are you looking for?

You might be looking for...

Una mirada contracatastròfica

Joan Yago and Enric Puig

I’m reading Contra la Distopía (Against Dystopia), the latest book by Francisco Martorell Campos, whose Soñar de otro modo (To Dream Differently) I really loved. A few pages in, I come across a question:

What stories are we telling ourselves? What political effects do they have? Telegraphic response: we tell ourselves dystopian stories that, against their will or not, amplify dismay and distrust. [...] But the generality of dystopias, even the most penetrating and socially committed, they merely reaffirm to those already convinced and add a few more arguments.

I close the book. And, as I come out of the metro, I think that we can only create what we’re able to imagine, and I wonder whether, in a present where counter-catastrophic imagination has become (as well as frankly exhausting) uncommercial, can we still create new things. It’s a question I ask myself obsessively; practically every day. I wonder if it makes sense to try and create and then I wonder what would be the point of stopping. It’s raining. I go through the door of a former 12th-century convent as I remember Andrei’s words in Three Sisters (Anton Chekhov, 1901):

The present is repulsive, but when I think of the future how wonderful things become! There’s a feeling of ease, of space; and in the distance there’s a glimmer of the dawn, I see freedom, I see myself and my children freed from idleness […], from goose with cabbage, from a nap after dinner, from the ignoble life of a parasite.

I’m inside. For the next sixty minutes I’ll try not to think about the end of the world.

Pieces

1. Nikolas Gomes, Concerto para Piano e Pandemia ![]()

Metabolising the surfeit of information through the senses, learning to walk in the storm. The composer speaks of “feeling the data instead of trying to make sense of it rationally”. I smile when I think that, having reached such a level of complexity, the only way to optimise our processing capacity is precisely to give way to the ancient mystery of melodies and rhythms. I think of a man I saw a few years ago on telly: he maintained he could read QR codes just by looking at them, like some ancient telluric which can be learned with time and patience.

Structurally, there’s no discernible difference. Life and death are unquantifiable abstracts. Why should I be concerned? - Dr Manhattan (Watchmen)

I think of J.G. Ballard’s silent droughts and floods, of the happy tropical apocalypse in “(Nothing But) Flowers” by Talking Heads. Is that a catastrophic thought? Oof. Maybe it is. Humanity – I say to myself – is beautiful, but in no way is it necessary. From a structural point of view, neither is life. Nature, in its most indomitable and inert form, is already an unparalleled creation, a breathtaking wonder. I keep walking.

6. Sara Dean + Beth Ferguson + Marina Monsonís, Tools for a Warming Planet ![]()

According to the creators of this piece, “This collection aims to provide tools to respond urgently to our planet’s uncertain future through art, activism and technology”. I think the epic prep is always rolled out in post-catastrophic scenarios, when the relentless collapse has swept aside the weak and the smoke of the mushroom cloud starts to dissipate. Why not think of pre-apocalyptic prepping? Or, even, as the creators propose, anti-apocalyptic. Do you have the tools to change the world? Well, don’t think that stockpiling them in a bunker five metres underground will do you any good. Get them out, share them and make sure you use them until your strength runs out.

7. Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean ![]()

I’ve always felt a profound admiration for people who cry. Who know how to cry. When I was little, tears were flames: destructive forces that adults had to protect us from and had to hurry to extinguish. I was unaware at the time that the flames could also keep us warm or boil water, as I was unaware that tears contain natural painkillers. I smile. I start laughing. I think of the astronauts on the International Space Station; of the powerful technology they’ve invented to extract oxygen from their own urine. I say to myself: “We’ll be unbeatable the day we learn how to recycle sadness. To use it to grow food, to charge our phones.” I stay like that for a while, smiling like an idiot.

9. Nooroa Tapuni,Waiting for Other ![]()

I read an article once about the nations of the Iroquois Confederacy and their “seventh generation principle”. This sacred law established that before making any significant decision (felling trees, declaring war, etc.), the chiefs had to consider the effects it would have seven generations into the future and only act if the effects were positive or harmless. The article was on a website of questionable reliability, but the fact is that I haven’t bought a plane ticket or hired a car since without thinking, even just for a second, about the people who’ll be living in the world 140 years from now. An idea occurs to me: “The ghosts that accompany us are not behind us, in the past. They’re in front of us.” It’s getting late, I move on.

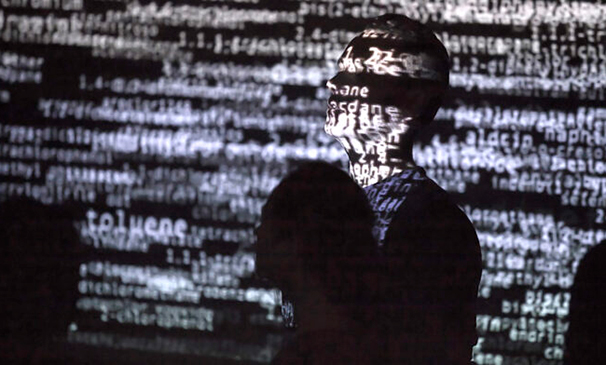

10. Joelle Dietrick, Tally Saves the Internet ![]()

One day we’ll tell our grandchildren that, when we were young, our mobile devices listened to our conversations and recorded private data without our consent, that they even did it when they were switched off. And how will our grandchildren react to this news? Will they throw their hands up in outrage? Or raise their eyebrows, surprised at the idea that devices in our day “could be switched off”? I think about the internet. How we use the internet. I imagine a road zigzagging along the coast sixty years in the past. A family of four is speeding along on a rickety moped. None of them are wearing a helmet. None of them are frightened. It’s a romantic image, tender and terrifyingly irresponsible. I really sympathise with Tally, with her big curious eyes, and a phrase comes to mind, no doubt from a film: “Life’s about fighting monsters.”

12. Marina Núñez, Still Life (Tornadoes) & Still Life (Swell) ![]()

I’d never realised the harshness of the term “still life”. According to Wikipedia, it features “commonplace objects which are either natural (food, flowers, dead animals, plants, rocks, shells, etc.) or man-made (drinking glasses, books, vases, jewelry, coins, pipes, etc.)”. Adding that it “occupied the lowest rung of the hierarchy of genres, but has been extremely popular with buyers”. It had been a while since I’d thought about the catastrophe, the inevitable catastrophe, but these vibrant, tempestuous paintings have brought it to the fore again. And it’s so beautiful... I think about the term “still life”. I raise my eyebrows and think that it could mean “motionless life”, but it could also mean “life, even now”. And as I approach to get a closer look at the natural forces caught in delicate glass vessels, I think “life, even now” and I’m almost convinced that, if I sit still for a while, now I could shed a tear. One as big and vibrant as an ocean.

Enric Puig Punyet

Doctor of philosophy and researcher specialising in the analysis of the new functions of institutions in the digital turn. He is currently director of Santa Mònica, and was previously director of the creation factory La Escocesa, where he promoted several research projects and the CO- Project, an institutional response to the Coronavirus pandemic. He has extensive experience as a university lecturer and curator of exhibitions, festivals and cycles on subjects related to the visual arts, film, philosophy and the changes that digitalisation has brought about in society and culture. At the CCCB, he promoted Enter Forum. International Forum on Internet and Privacity, a congress on the internet, creativity and society. He is a regular contributor to various media such as Le Monde Diplomatique, La Maleta de Portbou and El Periódico de Cataluña. He is the author of the books La cultura del ranking (Bellaterra, 2015), La gran adicción (Arpa, 2016), El dorado. Una historia crítica de internet (Clave intelectual, 2017) and Los cuerpos rotos. La digitalización de la vida tras la covid-19 (Clave intelectual, 2020). He is also the author, with Yves Charles Zarka, of La tierra no nos pertenece (NED, 2017).

Joan Yago (Barcelona, 1987)

He holds a degree in Directing and Playwriting from the Institut del Teatre de Barcelona. He has written plays such as De què parlem mentre no parlem de tota aquesta merda (Butaca Award for best text 2021), Els Ocells (2019), Sis personatges - Homenatge a Tomás Giner (2018), Fairfly (Max Awards 2018 for best new playwright and best new show, Butaca Awards 2017 for best text and best small-format show. Critics' Prize 2017 for best small-format show), You say tomato (Serra d'Or Critics' Prize for best theatrical text 2016), Un Lloc Comú (Bromera Ediciones - City of Alzira Prize 2014), Bluf (Quim Masó Prize 2014), Sobre el fenomen de les feines de merda (2015), Aneboda-The Show (2014), La Nau dels Bojos (Adrià Gual Award 2012), L'Editto Bulgaro (2012), Martingala (2012), República Bananera (2012), No sóc Dean Moriarty (2011), and Feísima enfermedad y muy triste muerte de la reina Isabel I (Audience Award and Jury Award at Fira Escènia 2010). He is also the creator and scriptwriter of the series Mai neva a Ciutat (IB3) and the medium-length film Snegovik (El Terrat-TV3).

Visit continues: https://santamonica.builders/isea/utopies

Other itineraries you can do:

- On monsters, ghosts, zombies and other terrifying beings, Paula Bruna and Marta Gracia Valladares ![]()

- (Un)wanted Spacetimes, Daphne Dragona and Jara Rocha ![]()

- Technologies for the festivals of the multiple ends, Paz Peña O. ![]()

- States of emergency: art in times of pandemic, Israel Rodríguez Giralt ![]()

- An enemy like the future, Ian Alan Paul ![]()

- Group Contraimaginarios Postpandémicos ![]()